TL;DR

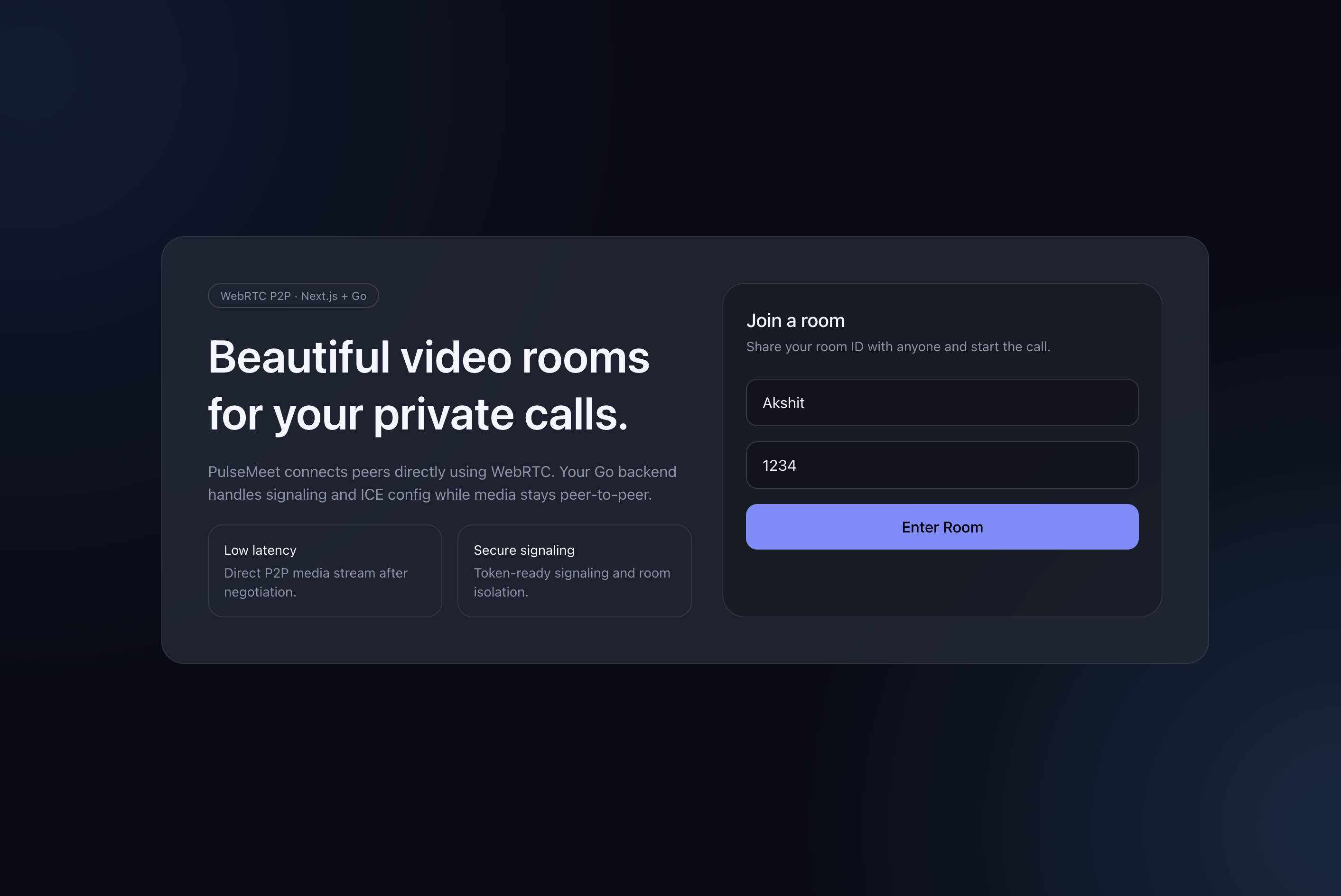

We built PulseMeet — a peer-to-peer video conferencing app from scratch using Go (signaling server), Next.js (frontend), and WebRTC (direct media). This article covers the why and how behind every architectural decision: how browsers discover each other through STUN/TURN, why your signaling server never sees video data, how to handle NAT traversal in the real world, and the subtle bugs that make WebRTC deceptively hard. Code is included where it matters, but the focus is on understanding the system.

Introduction

Video calling feels like magic. You click a link, grant camera access, and suddenly you're face-to-face with someone across the world. But underneath that simplicity lies one of the most complex real-time communication stacks in modern software engineering.

Most developers reach for hosted solutions — Twilio, Agora, Daily.co — and for good reason. Building video conferencing from scratch means wrestling with NAT traversal, codec negotiation, network topology detection, oce candidate trickling, ofer/answer state machines, and graceful degradation when networks fail.

But understanding how it works at the protocol level is incredibly valuable. It changes how you think about real-time systems, networking, and browser capabilities. So we built PulseMeet — not as a Zoom replacement, but as a learning artifact that's production-structured enough to deploy.

The stack:

- Go for the signaling backend (WebSockets, room management, rate limiting, Prometheus metrics)

- Next.js for the frontend (pre-join lobby, device selection, connection quality monitoring)

- WebRTC for direct peer-to-peer audio/video

- Docker for deployment with optional TURN relay support

Let's start with the fundamentals.

Get Full End to End Project Code - here

How WebRTC Actually Works

WebRTC (Web Real-Time Communication) is a set of browser APIs and protocols that enable direct peer-to-peer media streaming — audio, video, and data — without routing through a central server. It's built into every modern browser and requires no plugins.

But here's the critical misconception: WebRTC is peer-to-peer, but it can't work alone. Browsers can't just find each other on the internet. They need help from three types of infrastructure.

The Three Pillars of WebRTC

1. Signaling — The Matchmaker

Before two browsers can talk directly, they need to exchange connection metadata. This is called signaling, and it's the only part you build yourself. WebRTC deliberately does not define a signaling protocol — you can use WebSockets, HTTP polling, carrier pigeons, whatever.

What gets exchanged during signaling:

- SDP (Session Description Protocol) — Describes what media the peer wants to send: codecs, resolution, audio channels, etc.

- ICE Candidates — Possible network paths (IP:port combinations) the peer can be reached at.

2. STUN — The Mirror

Most devices sit behind NATs (Network Address Translators). Your laptop thinks its IP is 192.168.1.42, but the outside world sees your router's public IP. A STUN server tells your browser: "Here's what your public IP and port look like from the outside."

This is called Server Reflexive Candidate discovery. It's a lightweight UDP request — Google runs free STUN servers at stun:stun.l.google.com:19302.

STUN works for ~80% of connections where at least one peer has a permissive NAT.

3. TURN — The Relay of Last Resort

When both peers are behind strict/symmetric NATs, direct connection is impossible. A TURN server (Traversal Using Relays around NAT) acts as a media relay — both peers send their audio/video to the TURN server, which forwards it to the other peer.

TURN is expensive (it carries all the media bandwidth) but essential for reliability. In production, ~15-20% of connections need TURN fallback.

The Connection Flow

Here's how two peers actually connect:

The key insight: once the connection is established, the signaling server is no longer involved. Media flows directly between browsers. Your server never sees or processes the video data.

ICE: The Connectivity Framework

ICE (Interactive Connectivity Establishment) is the protocol that orchestrates this whole process. It gathers candidates — possible network paths — from three sources:

| Candidate Type | Source | Example | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Host | Local network interface | 192.168.1.42:54321 | Only works on same LAN |

| Server Reflexive (srflx) | STUN server response | 203.0.113.5:54321 | ~80% of connections |

| Relay | TURN server allocation | turn-server.com:443 | ~100% (but adds latency) |

ICE tries candidates in priority order — host first (fastest), then server reflexive, then relay (most reliable but slowest). This process is called ICE candidate gathering, and it happens in parallel with the SDP offer/answer exchange through a process called trickle ICE.

SDP: The Media Contract

SDP (Session Description Protocol) is a text-based format that describes a media session. When Peer A creates an "offer," it's essentially saying:

"I want to send H.264 video at 720p, Opus audio at 48kHz, and here are my ICE credentials."

Peer B's "answer" says:

"I accept H.264 (but I prefer VP8), I'll send Opus audio too, and here are my ICE credentials."

The browser handles codec negotiation automatically — you just need to relay these SDP blobs through your signaling server.

Architecture Decisions: Why Go + Next.js?

Before diving into implementation, let's talk about why this stack.

Why Go for the Signaling Server?

The signaling server has a very specific job: manage WebSocket connections, route messages between peers, and handle room logic. It's a concurrent I/O-heavy workload — exactly what Go excels at.

- Goroutines — Each WebSocket connection spawns two goroutines (read pump + write pump). Go can handle hundreds of thousands of goroutines on a single machine.

- Standard library —

net/http,encoding/json,log/slog(structured logging since Go 1.21) are production-quality out of the box. - Single binary — Compiles to a static binary with zero runtime dependencies. Docker images are tiny (~15MB).

- No framework needed — The signaling server is simple enough that

net/http+gorilla/websocketis all you need.

Why Not Node.js / Python / Elixir?

You absolutely could use any of these. Node.js with ws or socket.io is the most common choice. But Go's concurrency model (goroutines + channels) maps more naturally to the "one connection = two concurrent loops" pattern of WebSocket servers. There's no callback hell, no event loop blocking concerns, and memory usage stays predictable.

Why Next.js for the Frontend?

The frontend needs are modest: a landing page, a room page with video tiles, and device management. Next.js gives us:

- App Router with server components (landing page is static, room page is client-side)

- TypeScript for type safety across signaling message types

- Tailwind CSS for quick dark-theme UI

- Easy deployment via Docker or Vercel

Part 1 — The Go Signaling Server

Project Structure

go-webrtc-video-conf/

├── cmd/server/main.go # Entrypoint with graceful shutdown

├── internal/

│ ├── config/config.go # Env-based configuration

│ ├── observability/

│ │ ├── logging.go # slog structured logging

│ │ └── metrics.go # Prometheus instrumentation

│ ├── server/

│ │ ├── server.go # HTTP server, routing, CORS

│ │ └── middleware.go # Recovery & rate limiting

│ ├── signaling/bus.go # Event bus (NoOp / Redis)

│ └── websocket/

│ ├── message.go # Message types & structs

│ ├── client.go # WS client read/write pumps

│ ├── hub.go # Room manager & message router

│ ├── handler.go # WS upgrade handler + auth

│ ├── validate.go # Message validation

│ └── rate_limiter.go # Per-connection limiter

├── Dockerfile

├── docker-compose.yml

└── go.modThe structure follows Go conventions: cmd/ for entrypoints, internal/ for non-importable packages. Every concern is isolated — config, observability, HTTP serving, and WebSocket logic live in separate packages.

Configuration: Environment-Driven

Everything is driven by environment variables with sensible defaults. This matters because the same binary runs in development (single instance, no TURN) and production (multiple instances behind a load balancer, TURN enabled, Redis for cross-instance signaling).

Key configuration areas:

| Config Group | Variables | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Server | PORT, HOST | HTTP listener address |

| CORS | ALLOWED_ORIGINS | Restrict WebSocket origins |

| Security | SIGNALING_TOKEN | Optional bearer token for WS auth |

| WebRTC | STUN_URLS, TURN_ENABLED, TURN_URLS, TURN_USERNAME, TURN_PASSWORD | ICE server configuration served to clients |

| Redis | REDIS_ENABLED, REDIS_ADDR, REDIS_CHANNEL | Cross-instance event bus |

| Limits | MAX_PEERS_PER_ROOM, MAX_HTTP_PER_MINUTE, MAX_WS_MESSAGES_PER_SEC | Rate limiting |

The config loader uses godotenv for .env file support and falls back to OS environment variables — standard twelve-factor app practice.

The Middleware Chain

HTTP requests flow through a layered middleware stack:

Each layer wraps the next as an http.Handler:

- CORS — Validates

Originheader against allowed origins. Critical for WebSocket security since browsers send the origin header on upgrade requests. - Recovery — Catches panics in handlers and returns 500 instead of crashing the process.

- Rate Limiter — Per-IP fixed-window counter (requests per minute). Health check endpoints are exempt so Kubernetes probes aren't throttled.

- Metrics — Prometheus counters and histograms for request count, latency, and status codes.

The Hijacker Problem

Here's a subtle bug we hit: when you wrap http.ResponseWriter for metrics collection, the wrapper doesn't implement http.Hijacker — which gorilla/websocket needs to upgrade the HTTP connection to a WebSocket. The fix is to explicitly delegate:

func (w *statusCapturingWriter) Hijack() (net.Conn, *bufio.ReadWriter, error) {

hijacker, ok := w.ResponseWriter.(http.Hijacker)

if !ok {

return nil, nil, errors.New("does not support hijacking")

}

return hijacker.Hijack()

}This is a common gotcha when building WebSocket servers in Go with any kind of middleware. If your WebSocket upgrades fail with "response does not implement http.Hijacker", this is almost certainly the cause.

WebSocket Signaling: The Core

The signaling system has three components: Messages, Hub (room manager), and Clients (connection handlers).

Message Protocol

All signaling uses a single JSON envelope:

type Message struct {

Type MessageType `json:"type"`

RoomID string `json:"roomId,omitempty"`

PeerID string `json:"peerId,omitempty"`

TargetID string `json:"targetId,omitempty"`

Data json.RawMessage `json:"data,omitempty"`

Error string `json:"error,omitempty"`

Timestamp int64 `json:"timestamp,omitempty"`

}The Data field uses json.RawMessage intentionally — the hub doesn't need to understand SDP or ICE candidate structures. It just relays the raw bytes to the target peer. This keeps the signaling server thin and protocol-agnostic.

Message types form a clear state machine:

| Message Type | Direction | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

join | Client → Server | Request to join a room |

room-joined | Server → Client | Confirmation with list of existing peers |

peer-joined | Server → Room | Notify room that a new peer arrived |

peer-left | Server → Room | Notify room that a peer disconnected |

offer | Client → Client (via server) | SDP offer for WebRTC negotiation |

answer | Client → Client (via server) | SDP answer in response to offer |

ice-candidate | Client → Client (via server) | ICE candidate for connectivity |

error | Server → Client | Error notification |

leave | Client → Server | Graceful disconnect |

The Hub: Room Management

The Hub is the brain of the signaling server. It maintains a map of rooms, where each room is a map of peer IDs to client connections:

type Hub struct {

rooms map[string]map[string]*Client // roomID → peerID → Client

mu sync.RWMutex

maxPeersPerRoom int

bus signaling.EventBus

metrics *observability.Metrics

instanceID string // for distributed event dedup

}When a client sends a join message, the hub:

- Checks if the room exists (creates it if not)

- Checks if the room is full (

maxPeersPerRoom) - Adds the client to the room

- Sends

room-joinedback to the new client (with a list of existing peers) - Broadcasts

peer-joinedto everyone else in the room

When a client disconnects:

- Removes the client from the room

- Broadcasts

peer-leftto remaining peers - If the room is empty, cleans it up

For signaling messages (offer, answer, ice-candidate), the hub simply stamps the sender's peerID and forwards to the targetID. No interpretation, no transformation — pure relay.

Client: The Read/Write Pump Pattern

Each WebSocket connection spawns two goroutines:

- ReadPump — Reads messages from the browser, validates them, and passes to the hub

- WritePump — Reads from a buffered channel and writes to the browser, plus sends periodic pings

This pattern is standard in Go WebSocket servers. It decouples reading and writing, prevents write contention, and enables clean shutdown:

// Simplified — the real implementation has timeouts, error handling, etc.

func (c *Client) ReadPump() {

defer func() {

c.Hub.Disconnect(c)

c.Conn.Close()

}()

for {

var msg Message

if err := c.Conn.ReadJSON(&msg); err != nil {

break // Connection closed or error

}

if !c.Limiter.Allow() {

c.Send <- Message{Type: "error", Error: "rate limit exceeded"}

break

}

c.Hub.HandleMessage(c, msg)

}

}The write pump also handles WebSocket ping/pong for keepalive — if a pong isn't received within 60 seconds, the connection is considered dead.

Validation & Rate Limiting

Every incoming message is validated before the hub processes it:

joinmessages must have a room ID matching^[a-zA-Z0-9_-]{3,64}$offerandanswermessages must have valid SDP dataice-candidatemessages must have valid candidate structures

Per-connection rate limiting uses a fixed-window counter (N messages per second). This prevents a single malicious client from flooding the hub with messages. The limit is configurable via MAX_WS_MESSAGES_PER_SEC.

Horizontal Scaling with an Event Bus

A single Go instance handles thousands of concurrent connections easily. But if you need multiple instances behind a load balancer, peers in the same room might connect to different instances.

We solve this with an Event Bus abstraction:

type EventBus interface {

Publish(ctx context.Context, event Event) error

Subscribe(ctx context.Context, handler func(Event)) error

Close() error

}Three implementations:

NoopBus— Does nothing. Perfect for single-instance deployments.LogBus— Logs events toslog.Debug. Useful for development.RedisBus— Uses Redis Pub/Sub to propagate signaling events across instances.

Each event carries a SourceID (the publishing instance's UUID) so the hub can ignore its own events — preventing echo loops. When the hub receives an external event from Redis, it routes it to local clients just as if it had received it from a local WebSocket.

ICE Server Endpoint

The frontend needs to know which STUN/TURN servers to use. Instead of hardcoding this, we expose a /ice-servers endpoint:

{

"iceServers": [

{ "urls": ["stun:stun.l.google.com:19302"] },

{ "urls": ["turn:1.2.3.4:3478"], "username": "user", "credential": "pass" }

]

}This way, enabling TURN is a backend config change — the frontend picks it up automatically.

Observability

Production systems need observability. We use:

- Structured logging via Go 1.21's

slogwith JSON output, configurable log levels - Prometheus metrics for HTTP request counts/latency, active WebSocket connections, and message throughput by type/direction

The metrics are exposed at /metrics and can be scraped by Prometheus and visualized in Grafana.

Part 2 — The Next.js Frontend

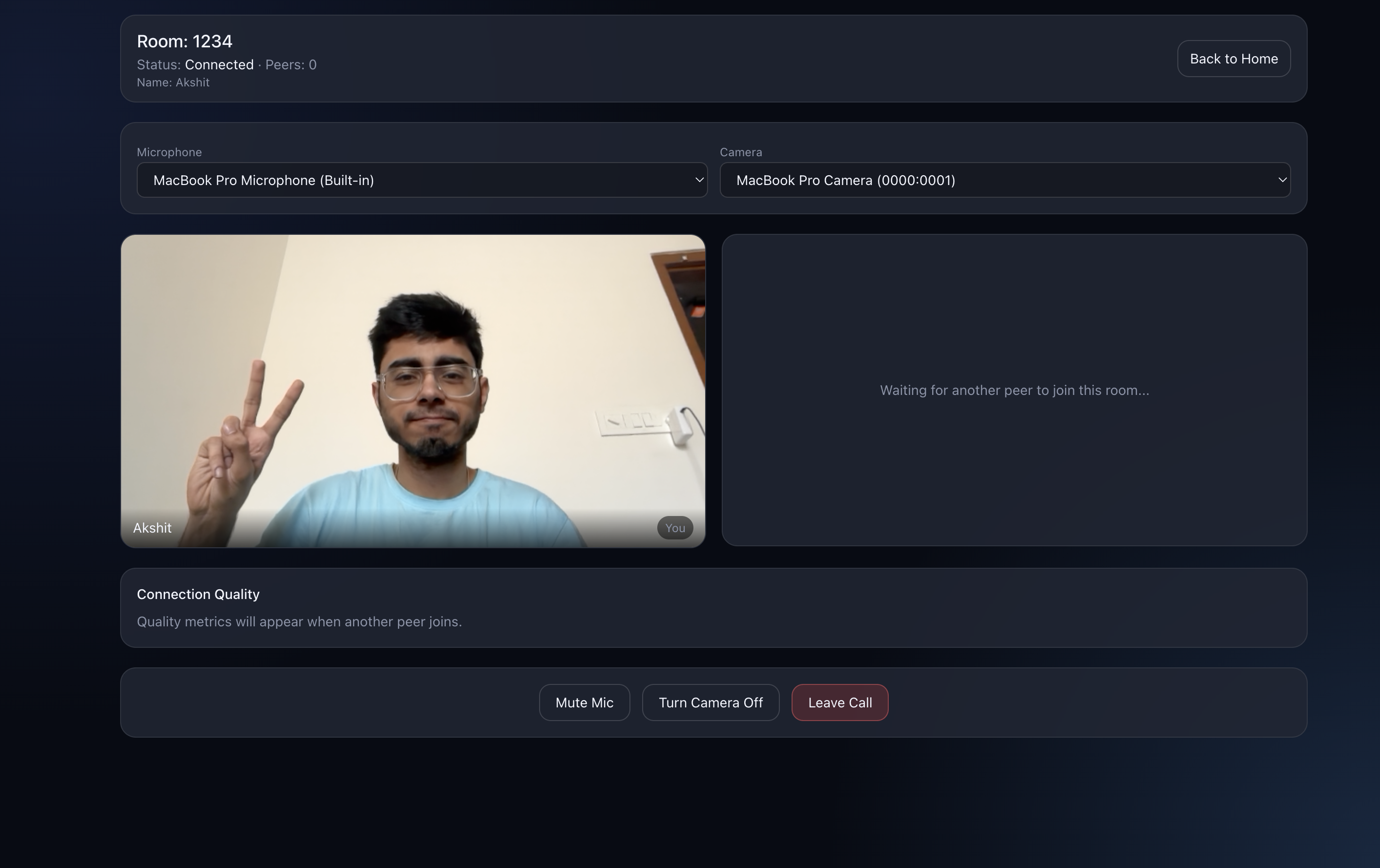

The frontend has three main responsibilities:

- Capture media — Get camera and microphone streams via

getUserMedia - Manage WebRTC connections — Create

RTCPeerConnectioninstances, handle SDP exchange, trickle ICE candidates - Render UI — Video tiles, call controls, device selectors, connection quality stats

Signaling Types

TypeScript types that mirror the backend message protocol:

export type SignalType =

| "join" | "leave" | "offer" | "answer"

| "ice-candidate" | "room-joined" | "peer-joined"

| "peer-left" | "error";

export interface SignalingMessage {

type: SignalType;

roomId?: string;

peerId?: string;

targetId?: string;

data?: unknown;

error?: string;

}Keeping these in sync with the backend is critical. A type mismatch in signaling messages is one of the most common sources of subtle WebRTC bugs.

The useVideoRoom Hook — Heart of the Frontend

All WebRTC logic lives in a single custom hook: useVideoRoom. This is the most complex piece of the frontend. It manages:

- WebSocket connection lifecycle (with auto-reconnect and exponential backoff)

RTCPeerConnectioncreation and teardown per remote peer- SDP offer/answer exchange

- ICE candidate trickle

- Media device enumeration and switching

- Connection stats collection

The Peer Connection Lifecycle

When a new peer joins the room, here's what happens:

The critical design decision here: only the existing peer creates the offer. When Peer B joins a room where Peer A already exists:

- Peer A receives

peer-joined→ creates the offer - Peer B receives

room-joined(with Peer A in the peer list) → waits for incoming offer

This avoids offer glare — a race condition where both peers create offers simultaneously, leading to conflicting SDP states and ghost connections. This was one of the hardest bugs we hit (more on this later).

Creating a Peer Connection

Each remote peer gets its own RTCPeerConnection instance:

const pc = new RTCPeerConnection({ iceServers: iceServersRef.current });

// Add our local audio/video tracks

localStream.getTracks().forEach((track) => pc.addTrack(track, localStream));

// When ICE finds a possible path, send it to the remote peer

pc.onicecandidate = (event) => {

if (!event.candidate) return;

sendMessage({

type: "ice-candidate",

roomId,

targetId: peerId,

data: { candidate: event.candidate.candidate,

sdpMid: event.candidate.sdpMid,

sdpMLineIndex: event.candidate.sdpMLineIndex },

});

};

// When remote media arrives, display it

pc.ontrack = (event) => {

const [stream] = event.streams;

setRemotePeers(/* update with new stream */);

};Handling WebSocket Messages

The WebSocket onmessage handler is a state machine that responds to each signaling message type:

room-joined— Store existing peer names, wait for offerspeer-joined— New peer arrived, create offer and send itoffer— Received an offer, create answer and send it backanswer— Received an answer, set it as remote descriptionice-candidate— Add the candidate to the appropriate peer connectionpeer-left— Close and clean up that peer's connection

Auto-Reconnect with Exponential Backoff

WebSocket connections drop. Networks switch. Browsers tab-sleep. The hook handles this with automatic reconnection:

socket.onclose = () => {

if (!shouldReconnect) return;

const attempt = reconnectAttempts + 1;

if (attempt > 6) { setStatus("error"); return; }

setStatus("reconnecting");

const delay = Math.min(1200 * attempt, 6000); // 1.2s, 2.4s, 3.6s... up to 6s

setTimeout(() => connectSocket(), delay);

};After 6 failed attempts, we give up and show an error state. In production, you'd likely add a "Retry" button at this point.

Device Switching Without Renegotiation

Users should be able to switch cameras or microphones mid-call without dropping the connection. WebRTC supports this via RTCRtpSender.replaceTrack():

const applyStream = (nextStream: MediaStream) => {

peerConnections.forEach((pc) => {

pc.getSenders().forEach((sender) => {

if (sender.track?.kind === "audio") {

sender.replaceTrack(nextStream.getAudioTracks()[0]);

}

if (sender.track?.kind === "video") {

sender.replaceTrack(nextStream.getVideoTracks()[0]);

}

});

});

};This swaps the underlying media track without triggering a new SDP renegotiation — the remote peer sees the switch seamlessly.

UI Components

The frontend consists of a few focused components:

Pre-Join Lobby

Before joining the room, users see a camera preview, can enter their display name, and select audio/video devices. This is critical UX — nobody wants to join a call with the wrong camera or a muted mic.

VideoTile

Each participant (local + remote) is rendered as a VideoTile — a <video> element with a name overlay and connection status indicator. The local video is always mirrored and muted (to prevent audio feedback).

CallControls

Mic toggle, camera toggle, and leave button. Simple, but with a subtle implementation detail: we use refs for the enabled state (not just React state) to prevent the main WebSocket effect from re-triggering when you toggle mic/camera.

Connection Quality Panel

We collect real-time stats from each RTCPeerConnection every 2 seconds using pc.getStats():

| Metric | Source | What It Tells You |

|---|---|---|

| Bitrate (kbps) | Delta of bytesReceived | Actual data throughput |

| RTT (ms) | currentRoundTripTime on candidate-pair | Network latency |

| Packet Loss (%) | packetsLost / packetsReceived | Network reliability |

| FPS | framesPerSecond on inbound-rtp | Video smoothness |

| Resolution | frameWidth × frameHeight | Video quality |

These metrics are classified into Good, Fair, or Poor quality indicators, giving users visibility into connection health.

Part 3 — Deployment with Docker

Multi-Stage Builds

Both the Go backend and Next.js frontend use multi-stage Docker builds for minimal production images.

Go backend — Compiles to a static binary in a builder stage, then copies it into a minimal Alpine image with a non-root user:

FROM golang:1.23-alpine AS builder

WORKDIR /app

COPY go.mod go.sum ./

RUN go mod download

COPY . .

RUN CGO_ENABLED=0 GOOS=linux go build -o /out/server ./cmd/server

FROM alpine:3.20

RUN adduser -D -H -u 10001 appuser

COPY --from=builder /out/server /app/server

USER appuser

EXPOSE 8080

ENTRYPOINT ["/app/server"]Final image size: ~15MB.

Next.js frontend — Standard three-stage build (dependencies → build → runtime):

FROM node:20-alpine AS deps

COPY package.json package-lock.json ./

RUN npm ci

FROM node:20-alpine AS builder

COPY --from=deps /app/node_modules ./node_modules

COPY . .

RUN npm run build

FROM node:20-alpine AS runner

ENV NODE_ENV=production

COPY --from=builder /app/.next ./.next

COPY --from=builder /app/public ./public

COPY --from=builder /app/node_modules ./node_modules

EXPOSE 3000

CMD ["npm", "run", "start"]Docker Compose Orchestration

A single docker-compose.yml brings everything up:

services:

server:

build: .

ports: ["8080:8080"]

env_file: .env

restart: unless-stopped

ui:

build: ./ui

ports: ["3000:3000"]

environment:

NEXT_PUBLIC_BACKEND_HTTP_URL: "http://localhost:8080"

NEXT_PUBLIC_SIGNALING_WS_URL: "ws://localhost:8080/ws"

depends_on: [server]

restart: unless-stopped

# Optional TURN server for NAT traversal

coturn:

image: coturn/coturn:4.6.3

profiles: ["turn"]

ports:

- "3478:3478/tcp"

- "3478:3478/udp"

- "49152-49200:49152-49200/udp"

restart: unless-stoppedRunning docker compose up --build starts both services. Adding --profile turn includes the TURN relay for remote connections.

Bugs We Hit & How We Fixed Them

Building with WebRTC is deceptively hard. Here are the most painful bugs we encountered.

1. The Hijacker Bug

Symptom: WebSocket connections fail with "response does not implement http.Hijacker".

Root Cause: Our Prometheus metrics middleware wrapped http.ResponseWriter for status code capture. The wrapper didn't implement http.Hijacker, which gorilla/websocket needs for the HTTP → WebSocket upgrade.

Fix: Explicitly implement Hijack(), Flush(), and Push() on the wrapper. This is a well-known Go gotcha but bites almost everyone building WebSocket servers with middleware.

2. Offer Glare — The Hardest Bug

Symptom: When two peers join simultaneously, both try to create offers. This causes conflicting SDP states, ghost peer entries, and one-way audio/video.

Root Cause: No clear "who creates the offer" convention. Both peers saw each other appear and both initiated negotiation.

Fix: Convention: only the existing peer creates the offer when a new peer joins. The new peer receives room-joined (with the peer list) but waits for incoming offers instead of creating its own.

Peer A joins → receives "room-joined" (empty peers list)

Peer B joins → receives "room-joined" (Peer A in list)

→ Peer A receives "peer-joined" → creates offer → sends to B

→ Peer B receives offer → creates answer → sends to AThis simple convention eliminates all offer glare issues.

3. Mic Toggle Creating Ghost Peers

Symptom: Toggling the microphone causes a full reconnect — new WebSocket connection, new client ID, duplicate peer entries.

Root Cause: isMicEnabled was in the useEffect dependency array for the main connection effect. Toggling mic changed state → re-ran the effect → disconnected and reconnected.

Fix: Use refs for enabled flags inside the effect, state only for UI rendering:

const toggleMic = useCallback(() => {

const next = !isMicEnabled;

micEnabledRef.current = next; // ref — doesn't trigger effect

stream.getAudioTracks().forEach(t => t.enabled = next);

setIsMicEnabled(next); // state — only for UI re-render

}, [isMicEnabled]);This is a common React pattern for WebRTC: use refs for anything the WebSocket/WebRTC effect reads, and state only for what the UI renders.

4. Stale SDP Answers

Symptom: During rapid reconnection, setRemoteDescription throws an error because the RTCPeerConnection is no longer in have-local-offer state.

Root Cause: A stale answer arrives after the connection has already been renegotiated or closed.

Fix: Guard the state before setting:

if (pc.signalingState !== "have-local-offer") return;

await pc.setRemoteDescription(answer);Always check signalingState before any SDP operation. The WebRTC state machine is strict and will throw if you violate it.

WebRTC in Production: What You Need to Know

NAT Traversal Reality

In our testing across different networks:

| Network Type | Direct Connection (STUN only) | Needs TURN Relay |

|---|---|---|

| Home WiFi (same network) | ✅ Always works | Never |

| Home WiFi → Office | ✅ Usually works | ~10% of cases |

| Corporate firewall → Corporate firewall | ❌ Often blocked | ~60% of cases |

| Mobile 4G/5G | ✅ Usually works | ~20% of cases |

| Behind symmetric NAT | ❌ Never works | Always needed |

Takeaway: If your app needs to work for everyone, you need a TURN server. Coturn is the standard open-source option.

Mesh vs SFU: Scaling Beyond 2 Peers

Our implementation uses mesh topology — every peer connects directly to every other peer. For a room of N peers, each peer maintains N-1 peer connections and sends N-1 copies of their media stream.

This works well for 2-4 peers but degrades quickly:

| Peers | Connections per Peer | Upload Streams | Total Connections |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| 3 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 4 | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| 8 | 7 | 7 | 56 |

For rooms with more than 4 peers, you'd want an SFU (Selective Forwarding Unit) — a server that receives each peer's single upload stream and selectively forwards it to other peers. This reduces upload bandwidth from O(N) to O(1) per peer.

Popular SFU implementations:

- Pion/Ion-SFU (Go) — fits naturally with our backend

- mediasoup (Node.js/C++) — battle-tested, used by many production apps

- Janus (C) — highly extensible, plugin-based

Security Considerations

| Concern | Our Approach |

|---|---|

| WebSocket origin checking | Validate Origin header against allowed origins list |

| Authentication | Optional bearer token on WebSocket upgrade |

| Message validation | Regex-validated room IDs, structured SDP/ICE validation |

| Rate limiting | Per-IP HTTP rate limiting + per-connection WebSocket rate limiting |

| DTLS encryption | Built into WebRTC — all media is encrypted end-to-end by default |

| Input sanitization | Room IDs restricted to alphanumeric + dash + underscore |

WebRTC media is always encrypted via DTLS-SRTP — this is mandatory in the spec. Even if someone intercepts the traffic, they can't decode the audio/video without the session keys.

Running the App

Local Development

1. Start the Go backend:

cp config.example.env .env

go mod tidy

go run cmd/server/main.go2. Start the Next.js frontend:

cd ui

cp config.example.env .env.local

npm install && npm run dev3. Open http://localhost:3000 in two browser tabs, join the same room — you should see video from both.

Docker (One Command)

cp config.example.env .env

docker compose up --buildDocker with TURN (For Remote Connections)

Set in .env:

TURN_ENABLED=true

TURN_URLS=turn:YOUR_PUBLIC_IP:3478?transport=udp

TURN_USERNAME=testuser

TURN_PASSWORD=testpassworddocker compose --profile turn up --buildWhat's Next

From here, you could extend PulseMeet with:

- Screen sharing —

getDisplayMedia()API to share your screen as an additional track - In-call chat — Send text messages through WebRTC Data Channels (bypasses the signaling server entirely)

- Recording — Use

MediaRecorderAPI to record calls client-side - SFU architecture — For 4+ peer rooms, integrate Pion/Ion-SFU or mediasoup

- Proper authentication — JWT-based auth instead of simple token matching

- Bandwidth adaptation — Use

RTCRtpSender.setParameters()to adjust video quality based on network conditions

FAQs

Does the signaling server see my video/audio?

No. The signaling server only relays connection metadata (SDP offers/answers and ICE candidates). Media flows directly between browsers via WebRTC. The only exception is if TURN relay is needed — in that case, the TURN server (not your signaling server) relays encrypted media.

Why not use Socket.IO instead of raw WebSockets?

Socket.IO adds reconnection, rooms, and broadcasting out of the box. But for a signaling server, raw WebSockets with gorilla/websocket in Go give us better performance, lower overhead, and full control over the protocol. Socket.IO's room abstraction also doesn't map perfectly to our hub/room model.

Can this handle 100 concurrent rooms?

Easily. Each room is just a map entry in the hub, and each WebSocket connection is two goroutines. A single Go process can handle tens of thousands of concurrent connections. The bottleneck is browser-side — each peer connection consumes CPU for encoding/decoding video.

Why is WebRTC so hard?

Three reasons: (1) NAT traversal is inherently complex and network-dependent, (2) the SDP offer/answer state machine has strict ordering requirements that cause subtle bugs, and (3) the browser APIs are low-level and error-prone. The protocol itself is well-designed — the difficulty is in the edge cases.

Do I need TURN in production?

Yes, if you want reliability for all users. About 15-20% of real-world connections fail without TURN, especially in corporate networks and behind symmetric NATs. Coturn is free and open-source, or you can use managed services like Twilio Network Traversal or Xirsys.

Conclusion

Building a video conferencing app from scratch teaches you more about networking, real-time systems, and browser capabilities than almost any other project. WebRTC is powerful but unforgiving — it rewards understanding the protocol and punishes shortcuts.

The key takeaways:

- Your signaling server is simple — it's just a message relay. Keep it thin.

- NAT traversal is the hard part — STUN handles most cases, TURN handles the rest. Always have a TURN fallback.

- Offer/answer ordering matters — Establish a clear convention for who creates the offer. Offer glare will ruin your day.

- Use refs, not state, in WebRTC effects — React's re-rendering model and WebRTC's imperative API don't mix well. Refs are your friend.

- Mesh topology has limits — For rooms beyond 4 peers, you need an SFU.

The full source code for PulseMeet is available on GitHub. Star it if you found this useful! ⭐